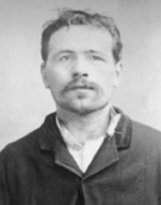

In Memory of François Claude Koenigstein (Ravachol)

In Memory of François Claude Koenigstein (Ravachol)

I.

Two gendarmes pushed François into the cell. The iron bolt slid shut behind him with an ear-splitting screech. It was the same cell in the provincial prison in Saint-Étienne at the end of the nineteenth century. The same thick walls of the old building. A small window under the ceiling with iron bars as thick as a finger. Through it, absolutely nothing could be seen—only a piece of the inner courtyard. It wasn’t even worth trying to reach it. But inside the cell, there was nothing to look at. A dirty straw pallet. A confined space: the same seven steps along and only four across. Deathly silence all around.

The authorities had taken unprecedented security measures when transporting him from Paris. And here at the trial—there were more guards than spectators in the hall. In the province of Loire, he was known less than in the capital. Even his friends had abandoned him. Perhaps because he preferred to act alone.

This couldn’t be happening. They couldn’t have done this to him. The state machine itself was breaking the law. He was not tried for what they wanted to execute him for in Paris. They didn’t let him say his last word—even though he had written a speech. Isn’t it the right of the accused to say everything he thinks about them all?

The jurors still dared to deliver a guilty verdict. And the judge was not afraid to sentence him to death. It was all over.

“Long live anarchy,” and that’s all he managed to shout after the verdict was announced. Now his fate was sealed. He knew it and couldn’t believe it. What would become of this world when he was gone?

François did not file an appeal—what was the use of arguing with a dishonest and simultaneously all-powerful state? That meant he would surely be executed any day now.

The fact that he was now waiting for death was reminded by the thick leather suit he was wearing, restricting the movement of his arms. So that he couldn’t take his own life. François plopped down on his pallet and plunged into his thoughts. He still couldn’t believe that his life was truly over and his days were numbered.

From somewhere far away, from the outside, came the annoying melody of a barrel organ, repeating in a loop. The voice of the organ grinder was not heard. And this made the music even more intrusive, repetitive, and banal. Just like his life once was.

François lay on his back. His gaze fell on the shabby ceiling. And he immersed himself in his memories. About how his father left the family when he was only eight years old. What year was that? Seems like 1867? He was left with only his mother, brother, sister, and an infant nephew. Since then, François had to work to support the family. As a shepherd in the village. As a dye worker in production. It was then that he, too, like someone far away outside the window, made extra money by turning the barrel organ. Indeed, his whole life was a barrel organ—François worked from dawn to dusk, then brought home what he earned. The money ran out before he earned anything again, and he was hungry and poor once more.

This is how millions of people live in the world, turning their barrel organ in a circle. But even then, François was different. He taught himself to play the accordion and performed at charity events in this very town, in Saint-Étienne, where he was now destined to die. François was not like other people. And even now, lying on a dirty pallet in a leather suit that restricted his movements, behind the iron bars of a small window, behind a steel door and a high wall of the city prison, he was freer than anyone else in all of France. And maybe in the world.

Because the boundary of freedom does not lie somewhere out there, beyond the fortress wall guarded by police. Not along the line of law or lawlessness. Not along the leather suit that restricts movements. And not even at the neck that François was to be severed by the guillotine by the court’s sentence. But somewhere inside, in the depths of consciousness, in the depths of the brain.

François lay staring at the ceiling, recalling his life full of deprivation and grief. Cold winter nights in the pastures in the Pilat mountains. The smell of manure surrounding him when he worked as a farmhand on the nearby farms. The hard work of a dye worker. And he realized that what he had done was still better than living like everyone else.

He remembered his first love. His first dates—walks through his hometown. The first kiss and that unforgettable night of love. Those distant secret meetings. And the news that she was marrying a richer man—one of the owners of the company where he worked, his boss.

His grandfather and father, François himself, and his family were always haunted by poverty and hunger. And this despite the fact that butcher shops, grocery stores around were overflowing with everything imaginable. If anyone was to blame for him becoming what he did, it was those people who made this world so different. For those who have money and everyone else who doesn’t and never can.

What did the factory owner think when he fired him for participating in the strike? Did he understand that François would have nothing to feed his family with? His beloved sister died then because there was nothing to pay the doctors.

Probably, it was in those days that François realized that all the needy have the right to take by force everything they need. That they are not obliged to wait for mercy from an indifferent society. And this would be much fairer than maintaining the existing social order, which threatens everyone’s life. It takes this life away.

He gathered with his friend and left for Lyon—to seek a better life. François remembered standing at the station of the big city, without money, without food. And thinking about how to earn at least something. And there, at home, his family, just as hungry as he was, waited for him, his closest ones.

Of course, he took on any job. But life wasn’t any better here either. And once again, losing his earnings, François returned home. Already without any hope that his work—a dye worker, steelworker, dry cleaner, whatever—would pull him out of the abyss.

It seems that it was during these days that he became an anarchist.

Life flashed in his memories like bright pictures on the ceiling. The solitary confinement of recent months kills life but develops imagination and imagery. François looked at this dirty ceiling and recalled himself, his loved ones, enemies, and friends. And gradually, the realization came to him that he had been sentenced to death. That he would be executed by the guillotine in the very near future.

II.

It is unknown how many hours he spent on his cot. But gradually, he became himself again. Strength and anger towards this world that made him who he was returned to him. And then condemned him to death for it.

Gradually, François got up. He began walking around the perimeter of his cell. Seven steps – three steps – seven steps – three steps. But this was no longer a circular motion. He had broken the repeating melody of the hurdy-gurdy long ago, back when he first became a criminal and then a revolutionary.

He knew that everything comes to an end someday. Everyone knows this. And if you ask a person what they would do if they had five years left to live, they would live their life differently. They wouldn’t waste it. François knew that everything would end. And so he used his life. He broke the vicious circle and breathed freely all these years.

With a terrible screech, the door bolt creaked, and a man in black robes entered the room.

“Hello, Mr. Ravachol, I am Abbot Claret. I have come so you can confess and prepare to meet the Almighty…”

“Father, if I believed in God, I would never have done all the things I’ve been sentenced to death for.”

But life left François no choice. The priest was the first and only person to visit him all these days, someone he could talk to. The state wasn’t satisfied with just killing the revolutionary, the authorities wanted to crush him, feared him, and thus it was strictly forbidden for the guards and policemen to communicate with him. So, François did not chase the abbot away but allowed him to stay. He wanted to convey to people, at least to this indifferent dressed-up holy man, who he was, why he was there, and what he was ready to die for.

“God is merciful, he will forgive you if you repent, you still have time…”

“I am not a criminal. The anarchists are right when they say that for universal peace to be established, the causes that generate crimes and criminals must simply be eliminated.”

“You will soon be executed…”

“It is useless to execute people like me. We can never be eradicated through repression. We will all die someday. It’s just that people like me, instead of dying a slow death from diseases and deprivations, prefer to take what we lack, even if it means risking our lives, which only bring us suffering.”

The priest pondered. In essence, he had nothing to say to this man. François wasn’t unhappy, he didn’t look doomed. There was an inexplicable strength in this man bound in skin.

“You are being executed not as a revolutionary but as an ordinary criminal…”

“And what would have changed if I had not been convicted now for killing and robbing a few wealthy old people who had been profiting from the labor of people like me all their lives? My family had nothing to eat when my friend and I broke into the tomb of Baroness Roche-Taille at the cemetery near Saint-Étienne. Why does the baroness need rings, a locket, a cross when she doesn’t need gold anymore? Just as I won’t need it – starting tomorrow.”

“But you didn’t just rob; you smuggled and engaged in other dirty deeds. You killed. You were convicted for the murder of a hermit in the Forez mountains and the theft of 35 thousand francs…”

“That’s because they couldn’t convict me as a revolutionary, a terrorist, and an anarchist. The authorities recalled and brought up an old criminal charge because they are always powerless against people like me. So the state has to act deceitfully. By the way, I couldn’t save even five francs through my righteous labor my entire life. Where’s the justice in that? And where did that unfortunate monk get such money?”

The priest did his duty, saving what he believed to be a lost soul. And yet he understood that what this man was saying was partly the truth. The terrible truth of our time. He still couldn’t understand who was in front of him: a maniac, a murderer and robber, or a revolutionary and terrorist.

“Do you really think you have the right to kill whoever you want?”

“You look at the world from the other side of the barricade. To eliminate crime, all that is needed is to eradicate poverty by simply giving people everything they need. For this, it is necessary to rebuild the world on new principles, to create a society where people are a united, friendly collective, where everyone, working according to their abilities, could consume according to their needs. Then, and only then, will there be no more victims or slaves of money. Then we will no longer see women selling themselves for money and men committing murder for it. The cause of all crimes is one, and you have to be a fool not to see it.”

Abbot Claret pondered. After all, who was in front of him? A thief and murderer? Or a revolutionary fanatic? He often had to hear the confessions of those sentenced to death. But these were entirely different people. Frightened, broken. And this young man gave the impression of being cynical and calm. Probably, this is how real heroes should be. If only the abbot didn’t know what this man had done in his life.

And while the priest standing next to him, disdainfully looking at the dirty straw bed, was thinking about something of his own, François suddenly realized that his life would end not today – but tomorrow. And his initial confusion, which had plunged him into deep memories just a few hours ago, was replaced by genuine anger. At this world. At those who rule it. At this well-fed and complacent dressed-up man, who was too disgusted to sit on his straw and perched somewhere on the edge.

“It’s a pity I managed to do so little! Now it’s all over. And I can tell you a lot.”

The priest knew from newspapers that François had started studying anarchism at the age of 18. That he had personally met those who participated in the Paris Commune. Yes, these people were national heroes once. But ten years later – only a group of theorists remained. Those who only talked about terror and retribution. And here was the man who had taken action himself. Completely alone.

“Yes, if I had killed and robbed a few bourgeois to feed my family, I wouldn’t consider myself a criminal. But I also wouldn’t be who I am. After all, it was I who stole 30 kilograms of dynamite from the coal mine warehouse near the town of Saussy-sous-Étiolle on February 15, 1892. My friends might never have had the courage to do this. To blow up this world.”

Abbot Claret knew this story. All of France knew it. It was printed in all the newspapers. The first explosion took place on March 11, 1892. Several flights of stairs collapsed in the building at 136 Boulevard Saint-Germain. Paris shuddered from the blast wave. The examination confirmed that the remains of the bomb, filled with buckshot, were directly related to the theft at the mine. It was revenge on the judge who conducted trials against anarchists involved in the May 1st demonstration a year earlier, demanding an eight-hour workday. Only by pure chance did the servant of justice survive.

But only four days later, a second explosion occurred. This time, a bomb was placed on the windowsill of the Lobau barracks, where 800 municipal guards—local police—resided. It didn’t matter that, by sheer luck, no one died again. This was a direct challenge to the authorities: a terrorist attack in the very heart of the city, near the city hall and the mayor’s office of the fourth arrondissement of Paris. It targeted those who were supposed to uphold law and order. In reality, all of Paris watched as they scurried around the half-destroyed building, like ants near a ruined anthill, terrified.

All efforts were mobilized to find those responsible. Arrests and searches among anarchists and the entire opposition led to nothing. Only through betrayal did the police discover who was behind the explosions. It turned out to be François, the man before him.

The first attempt to arrest François nearly cost the police their lives. He managed to escape and booby-trapped the house he was living in.

By this time, Ravachol’s name had become notorious. All of Paris knew him. They feared him. They loved him. Newspapers published François’s biography, recounting how a simple worker, a dyer, became a revolutionary who rocked France. In just a few days, he gained followers all over the country. Thanks to him, the revolution entered a new phase—individual terrorism. Many revolutionarily inclined French people realized that even if the time for overthrowing the current government and establishing a more just society had not yet come, they could blow up what existed now and those responsible for it, representatives of the state. Here and now.

But François didn’t just set off bombs. He also took responsibility for them. He found ways to communicate with journalists. Abbé Claret remembered his interview in one of the central newspapers, where François said: “We are not liked. But it must be understood that we, essentially, desire nothing but happiness for humanity. The path of revolution is bloody. I will tell you exactly what I want: first of all, to terrorize the judges. When there is no one left who dares to judge us, then we will begin to attack financiers and politicians. We have enough dynamite to blow up every house where a judge lives.”

And his words matched his deeds. Just a few days after his famous interview, Prosecutor Bulot’s house, who had prosecuted anarchists, was blown up. This happened on Rue de Clichy. The explosion threw residents out of their beds. The entire district was awakened by the desperate cries of the tenants, calling for help through the windows, as the staircases had been completely destroyed. It seemed he could indeed blow up every house where a policeman or judge lived. Any representative of state power.

“Do you really think you have the right to kill, to decide for God who lives and who dies?” asked the priest.

“In all layers of society, we see people who, if not wishing death, at least wish failure for their neighbor, because this failure can improve their own position. Don’t industrialists wish death to their competitors? Don’t merchants want to be the only ones in their field to take all the benefits? And the hope of getting a job allows the unemployed to wait for someone to lose it. In a society where this happens, it is no surprise that the actions I am accused of are merely a logical continuation of everyone’s struggle for survival. This all leads to the thought: ‘If this is the order of things, can I hesitate in my choice of means if I’m hungry, even if it causes casualties?’ Do employers, when firing workers, worry about them starving? How can someone live in luxury while those nearby lack the essentials?”

Abbé Claret was not particularly wealthy. Therefore, he still retained some understanding that life around him was far from perfect. He came almost every day to this prison to hear the confessions of the condemned, to ease the souls of those headed to the penal colonies. Sometimes, deep down, he despised those he had to interact with due to his duties.

But there was something special about this man. The abbé couldn’t understand what it was. What this man said vaguely resembled Christianity, but at the same time, it was entirely different. It was a religion for a new era and a new century.

Claret no longer felt intolerance or hatred towards this man. It wasn’t surprising that François was not allowed to speak at his trial—this simple worker, criminal, and terrorist could persuade. The abbé didn’t even notice when all his disdain disappeared, and he was already sitting next to François on the straw of his pallet. Yet what Ravachol said didn’t align with his views on life and society.

“But there are other, lawful ways to achieve social justice,” the abbé insisted, “like increasing taxes on the wealthy, for example.”

“In our society, achieving justice is impossible. No law, not even an income tax, can change the order of things. Unfortunately, many common people think that if we acted as you say, life would be better. But this is the wrong path. For example, if we tax property owners, they will increase rent and thus shift the burden of payments onto those who earn money by working. As long as there is property, no law can limit the owners’ right to dispose of their property. And what can be done about this? Only the destruction of private property and the extermination of those who have appropriated all the goods of life for themselves. And when we do this, we will reject money altogether to avoid the possibility of accumulation in the future. Otherwise, sooner or later, it will lead to the return of the current regime.”

“But how can enterprises exist without owners?”

“Owners are unnecessary. These people are idlers maintained by our workers. Everyone should do something useful for society, perform the work they are capable of. Some will be bakers, others teachers, and so on. Without idlers, everyone would work less—just a few hours a day. People couldn’t stay idle, so everyone would find themselves in something. And there would be no place for laziness.”

“So all evil is from the owners, whom you hate so much you’re willing to kill?”

“No, the main evil, in reality, is money. It is the cause of all disagreements, all hatred. All aspirations. It creates property. If we no longer had to pay to live, money would lose its value. And no one could get rich. There would be nothing to accumulate, nothing to buy a better life than others. Without money, no laws would be needed. And there would be no owners. Many useless things would disappear, like accounting. There would be no one and nothing to report to. Other types of employment would disappear too, like government officials who produce nothing and give nothing to society. Anarchy is, above all, the destruction of property.”

“But isn’t there a place for God in your anarchist theory? Have you no faith left at all?”

“As for religion, it will be destroyed, with no reason for its continued existence. It will lose all moral influence over people. There is no greater absurdity than faith in a God who doesn’t exist. After death, everything ends. People should enjoy the life they have. But when I talk about life, I mean real life, not one where you have to work all day for a fattening master and still die of hunger.”

“You have an answer for everything…”

“Well, maybe I don’t know everything. Unfortunately, those like me, the working class, who have to toil from dawn to dusk to earn their bread, have no time to read books…”

So who was he? A thief and murderer or a revolutionary who would go down in French history? At times, the priest understood that in some ways, this obsessed man was right: society was unjust. That the world would change sooner or later. But there was a huge difference between him and this condemned man. All society, each of us, is limited in our actions. By religion and faith. Upbringing. The law. Ultimately, fear of criminal prosecution and punishment. Only this man, bound, closed behind thick stone prison walls, sentenced to death—broke all obstacles and boundaries. He was truly free. Capable of anything to achieve his goals. And above all, François was not alone. There were many like him. And their number was growing.

Even a single François was something the state clearly couldn’t handle. The authorities were powerless to stop the wave of terror that engulfed France. It was hard to imagine that all this could be organized by just one man. All the government could do was hold endless meetings. Prime Minister Émile Loubet held long discussions with the Minister of War and the Police Prefect. But they were powerless against an unprecedented revolution—a revolt of individuals.

He was arrested purely by chance: the owner of the “Berry” restaurant on Boulevard Magenta recognized him and informed the police. It took no fewer than ten people to restrain François and take him to the station. As he was being dragged away, he shouted, “Brothers, follow me! Long live anarchy, long live dynamite!” It took several days to get his first statements. He regretted nothing, except that he had done so little.

There was no one in Paris to judge him. Judges and jurors were too afraid. The restaurant where he was captured had already been blown up by his followers. The maximum François faced was life imprisonment and exile to New Caledonia. No one doubted that sooner or later he would be freed in a revolution or rescued by his comrades.

III.

Life had other plans. The era of criminology was dawning, and François was held accountable for his past criminal deeds. Already sentenced to life at hard labor, François was brought here, to Saint-Étienne, for trial on charges of robbery and murder. The authorities always manipulate the law to suit their purposes. And now, François was here, facing his last interlocutor, Abbot Claret, the only person allowed to speak with him. Because his words seemed more dangerous to the state’s repressive machine than dynamite.

“Will you really go to the scaffold without any repentance?”

“And what if I did repent? Would I be forgiven? I would ask for God’s forgiveness if it allowed me to continue my struggle. But it’s pointless. I don’t believe in God, and all your repentance means nothing to me. My friends, my comrades have abandoned me. But they will make themselves heard again. The world will still see a true revolution.”

“And you’re not at all afraid to face the Almighty?”

“We, Mr. Abbot, live only once and here, on earth, for there is no other life beyond the grave. And if this is our real and only life, then we must strive with all our might to get the most enjoyment from it. For that, money is required. And if there’s no money, then one must engage in acquiring it. That’s all there is to it!”

When the struggle for survival loses all meaning, some fall into weakness and apathy, others into cynicism and stubbornness. This wasn’t written in the case file, but the priest knew: François didn’t steal money for a carefree life. He spent only on the bare necessities from what he acquired. The rest he gave to the anarchist movement. If it hadn’t been for the shooting of workers in Fourmies and Clichy. And if the police, who fired the shots, hadn’t accused his friends of using weapons. Most likely, this latest evidence of the state’s and the authorities’ injustice was the final straw. It transformed a simple worker, a former criminal, and an anarchist of today into a terrorist and a people’s hero.

The abbot realized it was impossible to persuade François. There was no repentance in this man because he was right. And the longer he talked with him, the more Claret worried about his own beliefs. Therefore, continuing the conversation was pointless. And there was no one to confess.

IV.

They said their farewells. The door closed behind the priest, and the bolt clanged shut again. François felt an extraordinary sadness. Was it really all over? And there was absolutely nothing more that could be changed? The cell was enveloped in endless prison silence. Night was falling. François didn’t care. If nothing could be done, then the sooner it was all over, the better. What would happen after he was gone?

And why had no one done anything to save him? At the first trial, there in Paris, the representatives of justice had feared him much more than he feared death now. His friends had sent them threatening letters. The jurors couldn’t reach a verdict. But here, in his hometown, everything had changed. Had the people’s love and support abandoned him? Still, he didn’t care about that either. He had done everything he could. As best as he could. And beyond that—whatever would happen, would happen. After all, there was very little time left. One night. Just a few hours.

But still, would there ever come, after his death, an era of justice and equal opportunities for humanity? Would poverty for some and immense wealth for others ever be eradicated? Would workers ever be able to own what they create? To be the true masters of their production?

And would the state’s repressive machine, whose sole purpose was to keep everything as it was, ever collapse?

He didn’t know, couldn’t know the answers to these questions. After all, François was just a simple worker. An anarchist. A man who had managed to break the constraints of society. To punish those guilty of injustice. But now his mission was completely fulfilled. François had done what he could. He didn’t care anymore. He was ready for anything.

François lay down more comfortably on his cot. His strength had left him. He fell into a deep sleep, the sleep of someone who suddenly didn’t care about anything anymore.

But he didn’t get to sleep for long. Already at half past three, the door opened and four men entered. The prison warden, a doctor, the prosecutor, and Abbot Claret.

“Get up, Ravachol, your time has come!”

But François no longer cared. He had survived the anticipation of execution. And now all that was left was complete indifference and acceptance of what was to come. The only thing he replied was, “Well, that’s good!”

V.

They took off his leather suit, which had been restricting his movements, and offered him the clothes he wore during the trial. The sentence was read out once more. Then they offered him a drink—and he downed an entire glass in one gulp.

“Do you want anything else?” the prosecutor asked, in the manner of an executioner before an execution, aware of his guilt, shyly and obligingly. At first, François shivered slightly and was pale. But he quickly managed to pull himself together. He remained himself: the fearless Ravachol. His composure returned. He was still alive, and he was an anarchist-revolutionary.

“Yes, I want to say a few words to those who will come to my execution.”

“But there will be no one…” the prosecutor replied.

François did not know how much the authorities feared him, even condemned to death. That almost the entire city was cordoned off by gendarmes and police. That the state’s justice could not show him to the people, and therefore planned to kill him secretly, in the prison yard.

Instead of communion, he asked for another drink.

At that moment, Abbot Claret had a thought: “If they execute him now, at his 33 years, he will become a new saint for the anarchists. Or even the Jesus of the anarchists himself.”

They poured François another drink, and he downed another glass. He felt warm and calm inside. It was all over. The last thing left was to leave with dignity. He felt no fear. And even if he did, he hid it: he considered it humiliating to appear weak in front of his enemy.

The executioner appeared and began his preparations, which professional killers in the name of the law call the “toilet of the condemned”: they tightly bound his hands behind his back and cut off the collar of his shirt. A cold shiver ran through François at the touch of the scissors to his neck. But he restrained himself and showed no sign of it. François tried to talk to the executioner, but he paid no attention to him and silently did his job.

The procession went out into the street and loaded into a cart. It was absolutely dark outside. The authorities wanted to deal with him under the cover of night, without waiting for dawn. François began to loudly sing a revolutionary song. About how other times would come, about how those who were taking him would someday be in his place. “If you want to be happy, hang your masters and cut the priests to pieces.”

In less than a minute they arrived at the place of execution. The guillotine appeared before his eyes—hidden from prying eyes. The executioner’s assistant, with a trained movement, lifted the heavy forty-kilogram slanted blade to the top of the mast, about four meters from the ground. François climbed onto the scaffold himself. The executioner tied him to a horizontal board, then laid him face down on the horizontal surface and lowered the top plank onto his neck.

In less than a minute they arrived at the place of execution. The guillotine appeared before his eyes—hidden from prying eyes. The executioner’s assistant, with a trained movement, lifted the heavy forty-kilogram slanted blade to the top of the mast, about four meters from the ground. François climbed onto the scaffold himself. The executioner tied him to a horizontal board, then laid him face down on the horizontal surface and lowered the top plank onto his neck.

Ravachol knew that he was about to die. But he was also certain that he would be avenged. That after his death, anarchist-revolutionaries would continue his path. And it would become a practice: personal retribution against each representative of authority for what they personally had done.

“Long live the rev!..” A sharp pain pierced through François. The basket at the foot of the guillotine struck his face painfully. For at least another thirty seconds, his brain remained alive.

Perhaps in those moments, François’ entire life flashed before his eyes. And if there were a god in the sky, he would have shown him what would happen next. And François would have known that retribution did not take long. On December 9, 1893, in Paris, Auguste Vaillant threw a bomb from the balcony where the seats for the public were located, into the chamber of deputies of Paris. Twenty parliamentarians were injured. And the first thing Vaillant declared after his arrest was that it was done in retaliation for Ravachol. On June 24, 1894, in Lyon, the Italian anarchist Sante Caserio inflicted a fatal knife wound on the President of France, Sadi Carnot. The very next day his widow received a photograph of Ravachol, with the inscription on the back: “This is revenge…”

And also, if God had met François at the scaffold, he would certainly have told him that his life and death had raised thousands of people to individual protest. And not only in France. That in distant and almost unknown to him Russia, hundreds of high-ranking officials, judges, police officers, and executioners were killed by bombs, knives, and revolvers at the beginning of the twentieth century.

God would have certainly told François that the communism he talked about would not be built in the twentieth century. But everywhere in the world, where the authorities left no other way to fight for justice, where there would be no opportunity for an ordinary person to assert their rights, where the state would disperse the dissenters—everywhere there would be a place for the creation of the Black Guard. And in rising to fight for their rights, people would recall him, Ravachol, more than once.

But François never knew any of this. God did not meet him. Because there is no God. Ravachol was entering history. He was entering eternity.

His body, by tradition, was placed in the same basket where his head lay. And they carried him to the cemetery.

Somewhere in the distance, dawn was breaking. And the sky was turning bright red from the bloodshed. Of all those who died for freedom.

Aleksei Sukhoverkhov (c)